This Sunday, Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s epic graphic novel series Preacher finally makes its way onto the small screen, and for many viewers it’s going to be their first (and only) iteration. For the rest of us, we’re going into the television show knowing that it doesn’t matter how great it is—it’ll pale in comparison to the graphic novels.

For those not in the know, Preacher was created by writer Garth Ennis and artist Steve Dillon, with Glenn Fabry on the original covers. The series was published by Vertigo and ran from 1995 to 2000. Since then it’s generally occupied a spot in every “Best Graphic Novels” list, and for good reason. Ennis and Dillon cover a lot of territory and use a variety of styles, tones, and genres to tell their story but always make sure to keep the dark humor and biting sarcasm at the fore.

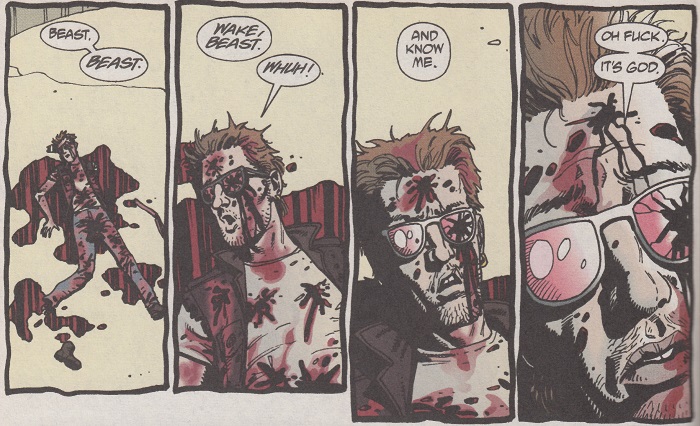

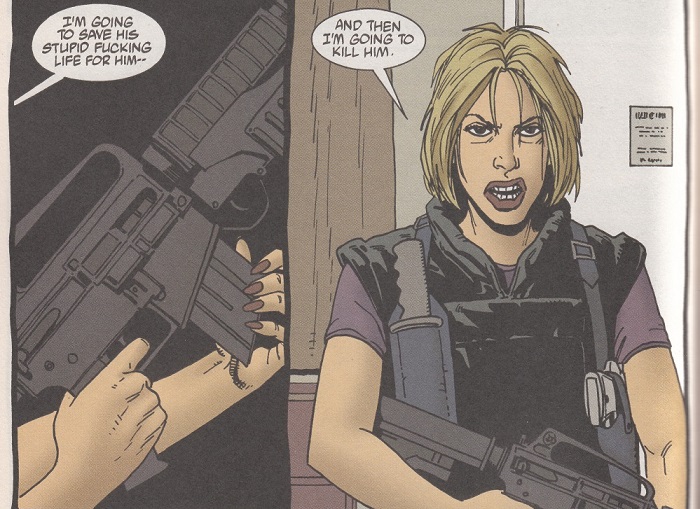

Ostensibly it’s about Jesse Custer, a drunken twentysomething preacher in the backend of Texas who is possessed by a spiritual entity more powerful than God. He soon sucks into his orbit Tulip, his on and off girlfriend, former car thief, and one-time hitwoman turned modern day Calamity Jane, and Cassidy, the drugged up, drunken Irish vampire and backstabbing BFF. As Jesse, Tulip, and Cass set off on a quest to confront God for abandoning his creations, Jesse gets tangled up in the terrifying force of will that are his wicked relations, a global religious conspiracy spearheaded by The Grail and the sadistic Herr Starr, and a gaggle of onlookers, stragglers, and sundry minor characters who push the story in directions not even our trio can predict.

It’s also surprisingly forward thinking for a bloody indie comic from the 1990s. Racists, sexists, and homophobes abound, but all of them are Big Bads that Jesse, Tulip, and Cass eagerly destroy. Jesse and Tulip regularly engage in debates about feminism wherein he listens to her plight and learns from his mistakes without #NotAllMen-ing or mansplaining. He may be from a deeply racist corner of Texas but Jesse holds to heart his father’s words of wisdom about judging people not by how they look but how they behave. (That being said, the ableism, fat shaming, and mocking of the developmentally disabled utilized by the stars and creators is cringe-worthy.)

The series starts out as an ol’ fashioned tale of good versus evil run through a Western grinder. It’s Stagecoach but with angels, vampires, and inbreeding. Jesse’s past drags him back to hell on earth and suddenly it’s a story about free will and destiny. Then a sharp left to the Vietnam War and the experiences suffered by Jesse’s father, John, and his best friend, Spaceman, and we’re in the realm of politics and patriotism and how the two states often contradict each other. Cassidy recounts his candy coated autobiography along with a rapid descent into the abyss of the Saint of Killers’ origin story and suddenly Preacher becomes a tale about how we want to be seen by those we love. Arseface, Hoover, Quincannon, and Starr reveal unique facets of revenge and redemption. Jesse and Tulip’s relationship post-France—and especially the arc about Tulip’s childhood—is all intersectional feminism, gender equality, and cultural respect but still manages to attack far left liberalism and far right conservatism with equal abandon. And the whole thing ends up a damn cowboy story once more.

No matter how gross-out or violent the story gets, at the heart of it Preacher is a love story. Sure, story-wise every topic under the sun gets its time to shine, but above all that are Arsefaced cupids with taut bowstrings ready to strike witting and unwitting couples alike. Love can be unrequited and foolish, dangerous and fragile, simple and welcomed, complicated and contented, misunderstood and fractured. Everyone wants love in Preacher, but most of them go about acquiring it in the most bone-headed ways possible.

This ain’t some starry-eyed 90s rom-com kinda “love.” This is real world love, love you have to work at, love that can make you a new person but not necessarily a better one. Jesse Custer and Tulip O’Hare have a love for the ages, a grand, Homeric tale of forgiveness, acceptance, and change that sprawls years and countries and deaths and resurrections. Yet even the platonic love front gets its strikes in. Jesse and Cassidy have a bond forged in battle but it’s too weak to stand up to Cass’ insecurities and moral failings, and still his final act is one born of a love too great to name. Tulip and Amy share a similar love but theirs is tempered only by time and distance, not competition or male bravado.

For Preacher love is the end, but violence of word, tone, and action is the means. Blood, nudity, cruelty, and derogatory terms stain nearly every page, yet even when the chaos veers toward gratuitous it always has a thematic point. Remember, Preacher is first and foremost a Western, and Westerns are romantic in both senses of the word. Love permeates Western tales. The love of a good woman can turn an evil man into a saint, and the loss of her can drive a decent man to savagery. A relationship between a man and his horse or a man and his partner is sacred, unbreakable, and worthy of revenge when stolen.

On the other side of the saddle is the mythology of the West. There’s a reason the word, the region, the idea itself is capitalized. The West is a place where myth and legend mingle with hard truths and mean realities. John Wayne and Louis L’Amour are the idealized end of the mythical West, with Unforgiven and Deadwood on the bloodsoaked extreme. But what they all have in common is the understanding that heroes never fret over doing good or bad. It’s doing what’s right that matters, even if balancing the scales means killing. Jesse confronts this truth with his own two opposites: the Saint of Killers and his hallucinatory John Wayne. The Saint damned himself and let his hate eat him alive while the Duke guides Jesse along the path of cowboy justice. Jesse wants God to atone for his crimes against humanity but isn’t above meting out his own justice against those who cross him or those he cares about. It’s the cowboy way. Hell, it’s the American way.

So yeah. In case I haven’t made it clear, Preacher is one helluva comic book. I’ve consumed it half a dozen times since I first stumbled upon it about a decade ago, and each time it gets better and better. Sure, it struggles now and then with a bloated, meandering plot. Sometimes the cast of characters gets a little too ungainly. It’s rife with curse words and inflammatory terms of the most racist, sexist, homophobic kind. And YMMV on the finale. (Frankly, I thought it was absolutely perfect, I mean, it’s a freaking Western for Hera’s sake. How could it have ended any other way?)

And yet. Preacher is a punch to the gut, a kick in the ass, heart-rending, teeth-grinding, mind-bending series that starts out dark and somehow gets even worse. It’s a powerful series with layers like a rotten onion—each one gets you closer to the truth but process gets messier the deeper you go.

Alex Brown is an archivist, research librarian, writer, geeknerdloserweirdo, and all-around pop culture obsessive who watches entirely too much TV. Keep up with her every move on Twitter and Instagram, or get lost in the rabbit warren of ships and fandoms on her Tumblr.

Spot on!

Currently on yet another re-read of the series before the TV show arrives, and it still delivers!!!

My biggest concern is that they’ll decide to pull punches on the religious aspects of the story, especially in the end.

I hope the TV series includes the Bill Hicks cameo.

Probably anyone reading this knows this will be on AMC.

So, I’ve been wanting to ask this for a while, but haven’t had the opportunity to talk to people who were actually fans of the comic, but I ragequit the series around volume 4 or 5 mainly because Jesse was a hypocritical, unlikeable asshole who I couldn’t cheer on in his blind rage against God. I was fine with Tulip and Cassidy.

Ah, where to start with Jesse. So, he is one of the most zenophobic, and homophobic hypocrites I’ve ever read. He is on a vendetta against God because the world is messed up, and then blames the French for atomic weapons, is pissed off that people don’t speak English because he can’t command them to kill themselves, and is a raging homophobe to boot. He’s on this “holy war” against God, and can’t seem to drum up any empathy for a single people group outside himself.

I also felt that some of the subjects for humor that Ennis was playing off just rings false in today’s age. It felt like he was making the joke to be transgressive, not to be funny. And it just comes off as zenophobic and homophobic in today’s day and age.

Am I completely off base with this? I enjoyed Cassidy and Tulip, but Jesse left a nasty taste in my mouth and I couldn’t continue the series when I wanted him to fail in everything he did because he was such an unlikeable character.

@5: I like Preacher OK, I did end up finishing it, but I definitely didn’t fall in love with it as hard as everyone else seemed to. There were definitely moments that turned me off of Jesse specifically, and I would disagree with the article that it only “veers toward” gratuitous. A lot of it did seem to be just for shock value, which I’m fine with in principle, but I just started to get tired of it by, I don’t know, two thirds of the way through. There was a lot of great stuff in that series, some of which this article highlights, but you have to wade through a fair amount of garbage to get to it too. But that’s just Garth Ennis, at least in my experience. Maybe it shows in Preacher more because people treat it as a modern classic.

@hihosilver28: Sounds like you substantially misunderstood Jesse. He’s not angry at the French for not speaking English, he’s mad he has to resort to killing them because he can’t Tell them to walk away. I also don’t know where you’re getting his blaming the French for bombing Monument Valley when he’s very clear about blaming Starr/the Grail for that. As for empathy, his storylines with Arseface, Lorie, and Billy Bob are ENTIRELY centered on his empathy and compassion toward them. Plus he feels guilty for misusing his Word with Hoover. He hates hurting people he knows don’t deserve it but will if they push him too far.

I’m not sure where you see the xenophobia and homophobia – he states repeatedly that he doesn’t care what people do as long as they don’t abuse their authority. If you mean you’re bothered by all the French jokes then I can see where you’re coming from, but accusing him of *hating* all non-Americans is a stretch. Starr is an asshole, the Allfather is evil, and Hahn killed people, so in cowboy justice they deserved what they got. And yes, there are a lot of borderline homophobic jokes, but they’re either made by the villains (in which case they get their comeuppance), by LGBTQ people themselves (we’re allowed to mock ourselves), or as examples of toxic masculinity and why the patriarchy hurts us all (everything Cassidy related).

I’ve also read a lot of Westerns so I can see where Ennis and Dillon are making specific commentary on niche tropes. The B-plot with the Mexican dude in Salvation plays with obvious contemporary racial issues but also is a smack in the face to the way Mexicans were treated in Western fiction. Same goes for all the “USA!” stuff.

As for the humor, keep in mind the series started in 1995. It was quite progressive for that time, but some of the jokes are off base 20 years later. I’m not sure we can really fault the series for that, but that doesn’t invalidate the offense.

@JeanTheSquare: Preacher is def a YMMV series. I know people who love it and who absolutely loathe it. Depends on how much you mind stories that wander off into the weeds – which I do very much. I could easily take several more issues exploring Amy’s backstory and walkabouts in sundry states that have nothing to do with his war on God. I like spending time with the characters and the world they inhabit more so than I care about getting back to the main arc.

@AlexBrown

I don’t think I fundamentally misunderstood Jesse. Perhaps in individual instances, but overall Jesse is a character who is pissed off at God for misusing His power and Jesse wants to bring God to answer for all of His (perceived) failings. Thing is, Jesse uses the Word against whoever he feels deserves it, and often just for pique, making him no better than God. Maybe that’s the whole point of the series, but I didn’t want to follow a protagonist who I’m supposed to root against when the series is cheering the decisions he is making.

Granted, this is just for the first 5 volumes, so maybe he becomes much less of an entitled asshole later in the series, but I didn’t have patience for him in those volumes. Which is a shame because I really enjoyed Tulip and Cassidy. I even felt for Jesse in his backstory volume when he heads back to the farm.

All of this said, I really want to check out the AMC adaptation, as it seems like they may have dropped the aspects of the books that I hated and kept the character building.